views

Reading Large Capacitors

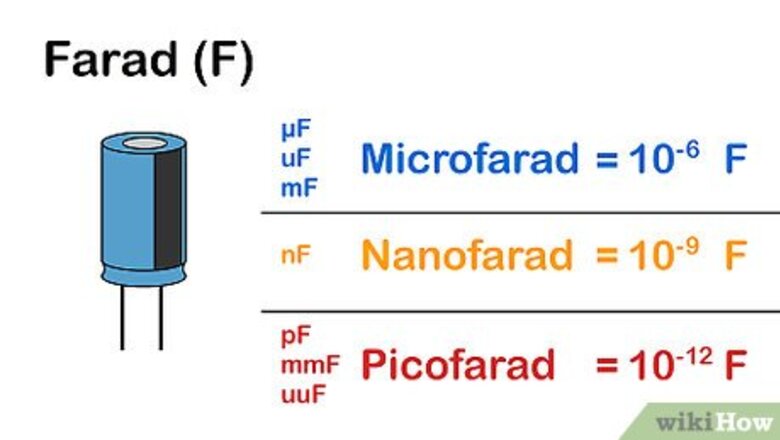

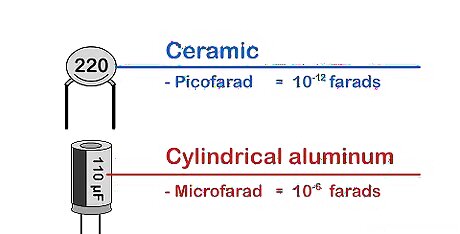

Know the units of measurement. The base unit of capacitance is the farad (F). This value is much too large for ordinary circuits, so household capacitors are labeled with one of the following units: 1 µF, uF, or mF = 1 microfarad = 10 farads. (Careful — in other contexts, mF is the official abbreviation for millifarads, or 10 farads.) 1 nF = 1 nanofarad = 10 farads. 1 pF, mmF, or uuF = 1 picofarad = 1 micromicrofarad = 10 farads.

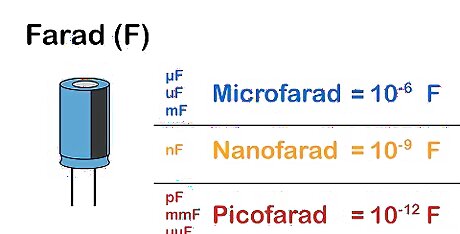

Read the capacitance value. Most large capacitors have a capacitance value written on the side. Slight variations are common, so look for the value that most closely matches the units above. You may need to adjust for the following: Ignore capital letters in the units. For example, "MF" is just a variation on "mf." (It is definitely not a megafarad, even though this is the official SI abbreviation.) Don't get thrown by "fd." This is just another abbreviation for farad. For example, "mmfd" is the same as "mmf." Beware single-letter markings such as "475m," usually found on smaller capacitors. See below for instructions.

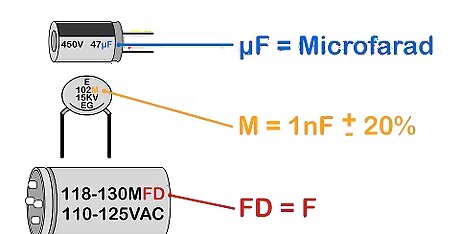

Look for a tolerance value. Some capacitors list a tolerance, or the maximum expected range in capacitance compared to its listed value. This isn't important in all circuits, but you may need to pay attention to this if you require a precise capacitor value. For example, a capacitor labeled "6000uF +50%/-70%" could actually have a capacitance as high as 6000uF + (6000 * 0.5) = 9000uF, or as low as 6000 uF - (6000uF * 0.7) = 1800uF. If there is no percentage listed, look for a single letter after the capacitance value or on its own line. This may be code for a tolerance value, described below.

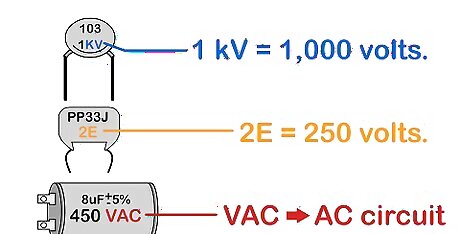

Check the voltage rating. If there is room on the body of the capacitor, the manufacturer usually lists voltage as a number followed by a V, VDC, VDCW, or WV (for "Working Voltage"). This is the maximum voltage the capacitor is designed to handle. 1 kV = 1,000 volts. See below if you suspect your capacitor uses a code for voltage (a single letter or one digit and one letter). If there is no symbol at all, reserve the cap for low-voltage circuits only. If you are building an AC circuit, look for a capacitor rated specifically for VAC. Do not use a DC capacitor unless you have an in-depth knowledge of how to convert the voltage rating, and how to use that type of capacitor safely in AC applications.

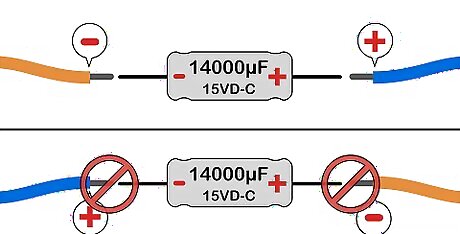

Look for a + or - sign. If you see one of these next to a terminal, the capacitor is polarized. Make sure to connect the capacitor's + end to the positive side of the circuit, or the capacitor could eventually cause a short or even explode. If there is no + or -, you can orient the capacitor either way. Some capacitors use a colored bar or a ring-shaped depression to show polarity. Traditionally, this mark designates the - end on an aluminum electrolytic capacitor (which are usually shaped like tin cans). On tantalum electrolytic capacitors (which are very small), this mark designates the + end. (Disregard the bar if it contradicts a + or - sign, or if it is on a non-electrolytic capacitor.)

Reading Compact Capacitor Codes

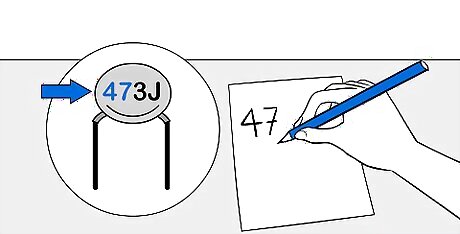

Write down the first two digits of the capacitance. Older capacitors are less predictable, but almost all modern examples use the EIA standard code when the capacitor is too small to write out the capacitance in full. To start, write down the first two digits, then decide what to do next based on your code: If your code starts with exactly two digits followed by a letter (e.g. 44M), the first two digits are the full capacitance code. Skip down to finding units. If one of the first two characters is a letter, skip down to letter systems. If the first three characters are all numbers, continue to the next step.

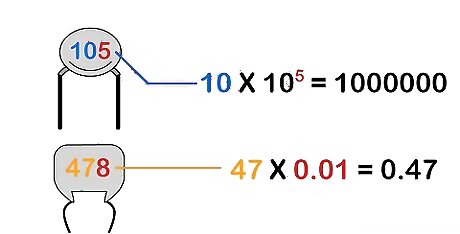

Use the third digit as a zero multiplier. The three-digit capacitance code works as follows: If the third digit is 0 through 6, add that many zeroes to the end of the number. (For example, 453 → 45 x 10 → 45,000.) If the third digit is 8, multiply by 0.01. (e.g. 278 → 27 x 0.01 → 0.27) If the third digit is 9, multiply by 0.1. (e.g. 309 → 30 x 0.1 → 3.0)

Work out the capacitance units from context. The smallest capacitors (made from ceramic, film, or tantalum) use units of picofarads (pF), equal to 10 farads. Larger capacitors (the cylindrical aluminum electrolyte type or the double-layer type) use units of microfarads (uF or µF), equal to 10 farads. A capacitor may overrule this by adding a unit after it (p for picofarad, n for nanofarad, or u for microfarad). However, if there is only one letter after the code, this is usually the tolerance code, not the unit. (P and N are uncommon tolerance codes, but they do exist.)

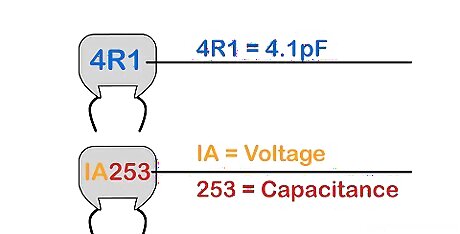

Read codes that contain letters instead. If your code includes a letter as one of the first two characters, there are three possibilities: If the letter is an R, replace it with a decimal point to get the capacitance in pF. For example, 4R1 means a capacitance of 4.1pF. If the letter is p, n, or u, this tells you the units (pico-, nano-, or microfarad). Replace this letter with a decimal point. For example, n61 means 0.61 nF, and 5u2 means 5.2 uF. A code like "1A253" is actually two codes. 1A tells you the voltage, and 253 tells you the capacitance as described above.

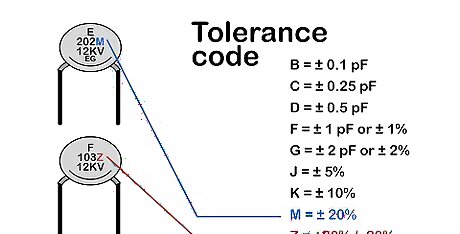

Read the tolerance code on ceramic capacitors. Ceramic capacitors, which are usually tiny "pancakes" with two pins, typically list the tolerance value as one letter immediately after the three-digit capacitance value. This letter represents the tolerance of the capacitor, meaning how close the actual value of the capacitor can be expected to be to the indicated value of the capacitor. If precision is important in your circuit, translate this code as follows:Read a Capacitor Step 10 Version 3.jpg B = ± 0.1 pF. C = ± 0.25 pF. D = ± 0.5 pF for capacitors rated below 10 pF, or ± 0.5% for capacitors above 10 pF. F = ± 1 pF or ± 1% (same system as D above). G = ± 2 pF or ± 2% (see above). J = ± 5%. K = ± 10%. M = ± 20%. Z = +80% / -20% (If you see no tolerance listed, assume this as the worst case scenario.)

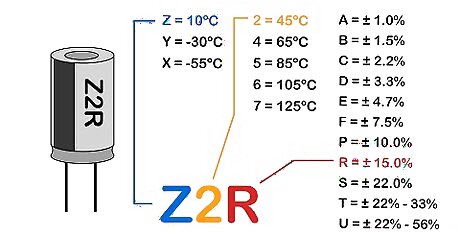

Read letter-number-letter tolerance values. Many types of capacitors represent the tolerance with a more detailed three-symbol system. Interpret this as follows: The first symbol shows minimum temperature. Z = 10ºC, Y = -30ºC, X = -55ºC. The second symbol shows maximum temperature. 2 = 45ºC, 4 = 65ºC, 5 = 85ºC, 6 = 105ºC, 7 = 125ºC. The third symbol shows variation in capacitance across this temperature range. This ranges from the most precise, A = ±1.0%, to the least precise, V = +22.0%/-82%. R, one of the most common symbols, represents a variation of ±15%.

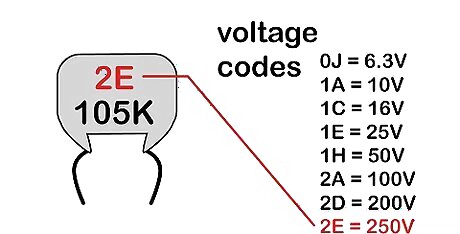

Interpret voltage codes. You can look up the EIA voltage chart for a full list, but most capacitors use one of the following common codes for maximum voltage (values given for DC capacitors only): 0J = 6.3V 1A = 10V 1C = 16V 1E = 25V 1H = 50V 2A = 100V 2D = 200V 2E = 250V One letter codes are abbreviations of one of the common values above. If multiple values could apply (such as 1A or 2A), you'll need to work it out from context. For an estimate of other, less common codes, look at the first digit. 0 covers values less than ten; 1 goes from ten to 99; 2 goes from 100 to 999; and so on. Restore electronics by replacing worn capacitors. "I have this old DVD player that randomly stopped working one day. After some research, I learned that Panasonic used low-quality capacitors in that model that tend to fail over time. This guide walked me through how to ID and replace those bad capacitors. Now my DVD player is working again! It saved me from having to buy a new one." - Barry B. Build a custom laser with salvaged parts. "I was trying to build my first ever 650 nm burning laser as a hobby project. I had gathered a mishmash of spare parts, including a bunch of unlabeled disc capacitors dug out of an old electronics repair kit. This article explained how to make sense of all the tiny capacitor codes so I could finally figure out which ones would work." - Mike B. Maintain railroad signal systems. "I used to work on voltage circuits for railroad signals and crossings. Even though I'm retired now, I still like to tinker and refresh my understanding. I often reference this guide when I come across older capacitors with odd markings I've forgotten how to decipher. It helps me double-check my work." - Sal D. Mod vintage guitars with found components. "My father-in-law gifted me a box of old capacitors he found in his attic. I've been using them to restore and mod vintage guitars as a hobby. With so many tiny unmarked components, I was totally lost at first. But this article has been my trusty guide for identifying capacitor codes and values. Now, I can finally experiment with custom tone controls." - Andy M. Have a story our readers should hear? Share it with 1 billion+ annual wikiHow users. Tell us your story here.

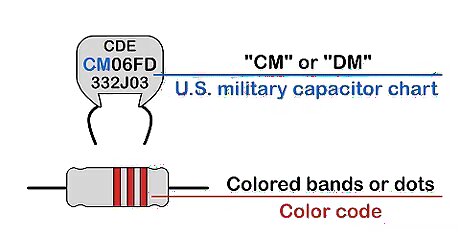

Look up other systems. Old capacitors or capacitors made for specialist use may use different systems. These are not included in this article, but you can use this hints to guide your further research: If the capacitor has one long code beginning with "CM" or "DM," look up the U.S. military capacitor chart. If there is no code but a series of colored bands or dots, look up the capacitor color code.

Comments

0 comment