views

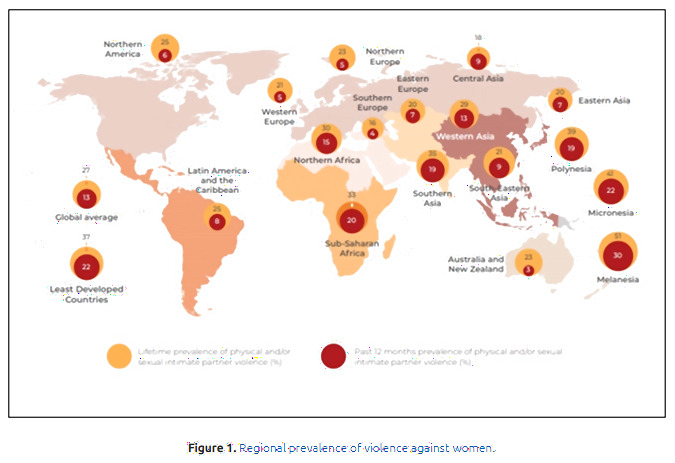

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), ‘violence against women remains devastatingly pervasive’ affecting around 736 million women worldwide. Women from low-and lower- middle-income countries are disproportionately affected by violence. About 37 per cent of women (15 to 49 years) in the poorest countries are subjected to violence, with high prevalence of domestic violence in South Asia and Sub Saharan Africa, nearly 33 to 51 per cent (figure 1). The lowest prevalence (16-23 per cent) was seen in Europe, Central and Eastern Asia regions.

The pandemic has further exacerbated violence against women, with particularly domestic violence showing an increase. The reasons include stress with loss of livelihood, disruption of social and protective networks, close living conditions, and restricted movement. The Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) on gender equality calls for an elimination of ‘all forms of violence against all women and girls in public and private spheres, including trafficking and sexual and other types of exploitation’. Yet 49 countries have no legislation on domestic violence. COVID-19 implications have led to a 30 per cent increase in domestic violence for some countries.

Violence has immediate effects on women’s health—physical, sexual and reproductive, as well as mental and behavioural. It increases the risk of maternal mortality and pregnancy-related consequences—low maternal weight and still births. Studies across countries—Nicaragua, Bangladesh, India, and the US—report high incidence of low birth weight babies and deaths amongst pregnant women due to domestic violence.

WHO conducted a multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women which showed strong associations between violence and both physical and mental symptoms of ill-health of women. Women exposed to domestic violence are 16 per cent more likely to have a low birth weight baby. Other than having a direct impact on women, domestic violence also affects children. Studies indicate an association of undernutrition amongst children in households having domestic violence. A review of demographic and health surveys from 29 low-and middle-income countries showed a strong association between stunting and domestic violence in both rich and poorly educated women. The impact of domestic violence gets further camouflaged with impacts of food insecurity, micronutrient deficiency, and limited access to sanitation in poor households.

Evidence from Latin America on domestic violence and child nutrition indicates adverse effects on a child’s long-term nutritional status. There is less likelihood of receiving pre-natal care, and the child being breastfed and immunised. A causal estimate of the intangible costs of violence against women in Latin America and the Caribbean suggests a negative link with women’s health, affecting both short-term health outcomes and the human capital accumulation of children.

However, women’s education and age tend to safeguard against the negative impact of violence on children’s health. The World Bank indicates that the cost of violence against women could come up to 3.7 per cent of the GDP. Studies from Bangladesh and Nepal show an association between violence and the nutritional status of women and a possible link to increased stress, poor self-care, and nutrition. A study on mother-child dyad from Pakistan shows a significant increase in underweight, stunted, and wasted children in women who are subject to domestic violence.

Findings from a demographic health survey in Bangladesh shows compromised child growth with a greater risk of stunting in children born to women subject to lifetime domestic violence. Community studies from Nicaragua and Bangladesh suggests improved women’s status to be strongly associated with improved child health and nutritional status. A regression analysis of data from Bangladesh, found domestic violence amongst others as a risk factor that contributes to child stunting. The impact of violence against women lasts for generations leading to grave demographic consequences hindering educational attainment and earning potential.

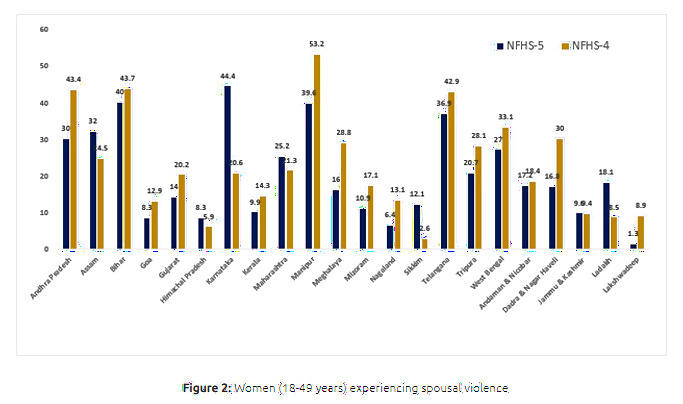

There is a growing concern around gender-based violence in India having significant economic and social costs. Past surveys indicate an increasing trend of domestic violence in India, despite it being a criminal offence under section 498-A of the Indian Penal Code. A study indicates increased probability of child stunting, underweight and wasting in children whose mothers experienced spousal violence. The findings from the 2019-20 NFHS-5 data indicates a decrease in the rate of spousal violence in many states and Union Territories (figure 2). However, Karnataka, Assam, Maharashtra, Ladakh, Sikkim, and Himachal Pradesh show increasing trends.

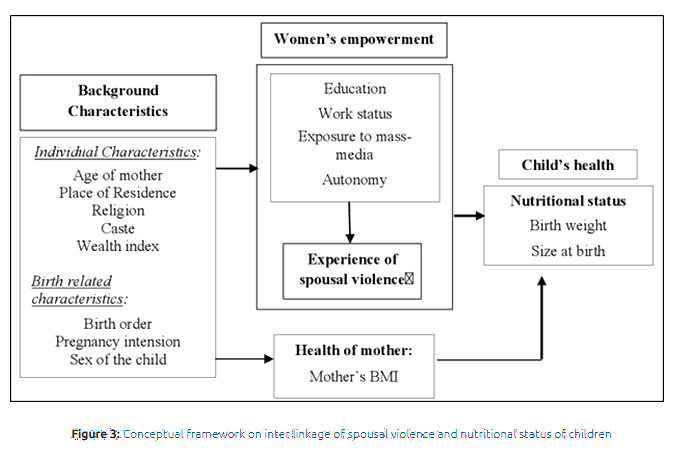

Atreyee Sinha and Aparajita Chattopadhyay have elicited the inter linkage between spousal violence and nutritional status of children through a conceptual framework (Figure 3). It relates how children’s health depends on mother’s empowerment and health status, and spousal violence is an important intermediate factor influencing child health.

Evidence indicates a direct causal relationship between domestic violence and growth and development of children with significant impact on child stunting and underweight.

The impact of violence is more evident in women not employed as to the employed and empowered. Domestic violence is a human rights issue and reducing its occurrence is contributing to ensuing health benefits. Above all, the pandemic has added to the challenge for adolescents girls (10-19 years) in access to essential services. The social and economic impact of COVID-19 has been profound for rural women who are further subjected to domestic violence, abuse, and malnutrition. Similar findings have been reported from rural and tribal communities from southern India.

Improvement in gender inequality could contribute to 10 percentage points decline in stunting prevalence rate in children. Also combining nutrition‐specific interventions with measures for empowerment of women is essential and imperative for reduction of child undernutrition. A randomised controlled trial in Mumbai slums suggest community mobilisation to address the public health burden of violence against women and girls. A systemic review on interventions to reduce domestic violence calls for effective communication-based and community-based interventions.

There is an urgent need for intensifying interventions and investing in reducing undernutrition, improving women’s nutrition and education, promoting gender equality, empowering women, and elimination of domestic violence against women to reduce the prevalence of malnutrition.

This article was first published on ORF.

Read all the Latest News, Breaking News and Coronavirus News here.

Comments

0 comment