views

X

Research source

The ophthalmoscope is a relatively simple tool that can be mastered if understood properly and with sufficient practice.

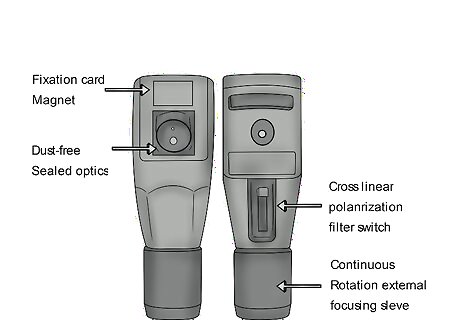

Preparing Your Instrument

Determine if the ophthalmoscope is working properly. Turn the power switch to the on position to check if the light works. If not, replace the batteries and try again. Look through the aperture (eyepiece) to ensure clarity. Remove or slide open the aperture's cover if one exists.

Select the appropriate setting. There are several aperture and filter options that can be used for specific goals in an eye examination. The most common setting used is the Medium light source, because most exams are done in a darkened room when the patient has not been treated with mydriatic (dilating) eye drops. Ophthalmoscopes may differ in which settings are available, but some possibilities are: Small light – for when the pupil is very constricted, like in a bright room Large light – for highly dilated pupils, like when treated with mydriatic drops Half light – when part of the cornea is obscured, like with a cataract, to direct light into the clear part of the eye Red free light – to better visualize the blood vessels and any problems with the vessels Slit – to check for irregularities in contour Blue light – to use after fluorescein staining to check for abrasions Grid – to measure distances

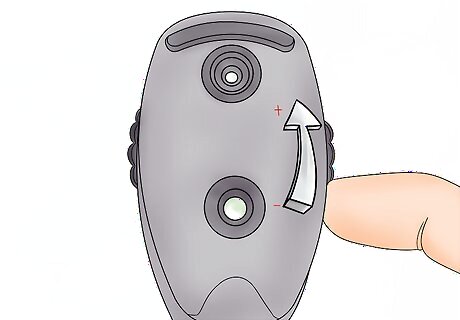

Focus the instrument using the focusing wheel. Generally, you should focus your ophthalmoscope to the “0” setting, which is the baseline. Be aware that focusing towards the positive numbers – sometimes marked on the instrument in green – focuses on things closer to you, and focusing towards the negative numbers – sometimes in red – focuses on things farther from you. For the PanOptic ophthalmoscope, focus using the focusing wheel on a point about 10-15 feet away from you.

Preparing Yourself and Your Patient

Explain the procedure to your patient. Have your examinee sit down in a chair or on the examination table. Tell them to remove their glasses or contacts if they’re wearing any. Explain what an ophthalmoscope is and warn the patient about the brightness of the light emitted. If you will be dilating the pupil with mydriatic drops, explain the procedure and effects, including that they should have someone drive them home after. You don’t have to go into much detail about the eye exam. Say something like, “I’m going to use this instrument to look into the back of your eye. It will be a bright light, but it shouldn’t be uncomfortable.”

Wash your hands. Gloves are not necessary for this procedure, but it’s standard practice to thoroughly wash your hands with soap and water before and after any type of physical exam.

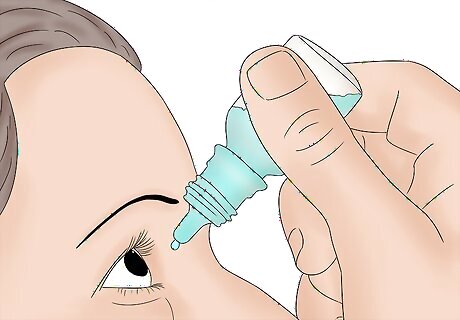

Apply mydriatic drops, if necessary. Dilating the pupils provides easier and more thorough visualization of the eye structures, and is used often in optometrists’ offices. Have the patient tilt their head back. Gently pull out their lower lid, and drop the appropriate number of drops into the eye. Have your patient close their eye for about 2 minutes, and press on the corner of their eye where it meets the nose. Do this in both eyes. Tropicamide 0.5% is most commonly used, applying 1-2 drops about 15-20 minutes before your exam. Other agents used are Cyclopentolate 1%, Atropine 1% solution, Homatropine 2%, and Phenylephrine 2.5% or 10% solution. All of these drops are contraindicated in patients with a head injury that is being monitored. Review a list of your patient’s medications to ensure they have no interactions with the eye drops. Darker eyes may be less sensitive to drops and require more than lighter-hued eyes.

Darken the room. Dim the lights considerably. Having extra lights on hinders the sharpness of the ophthalmoscope magnification. Remember, if you are unable to make the room darker, adjust the light setting on your ophthalmoscope accordingly.

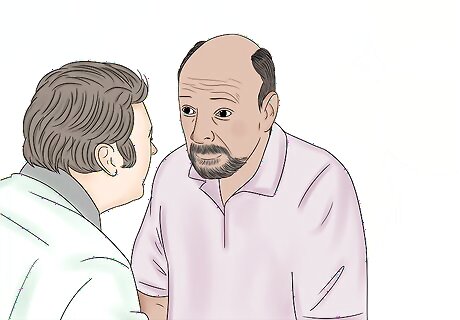

Position yourself in relation to your patient. You want to be eye-level with your patient, so stand straight, bend forward, or sit in a chair in order to be at the appropriate level. Position yourself at your patient’s side, and approach them from approximately a 45° angle.

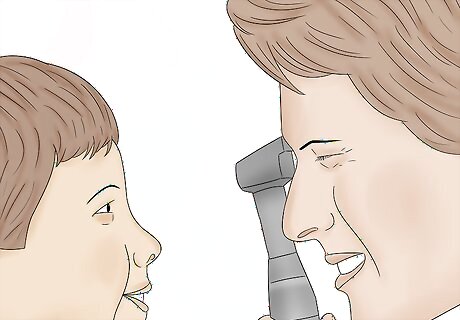

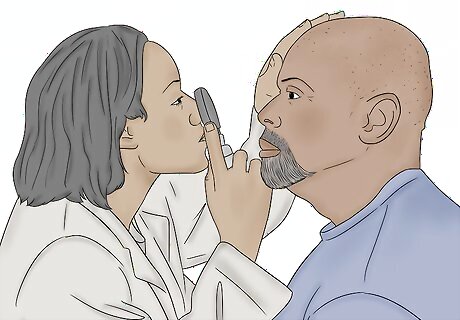

Situate your scope and approach to the patient correctly. Let’s say we first want to evaluate the patient’s right eye. Wedge the ophthalmoscope against your right cheek with your right hand – when you move, your head, hand, and scope should move as one. Place the heel of your left hand firmly on the patient’s forehead and spread your fingers out, providing stability. Position your left thumb gently over their right eye and lift the right eyelid open. Use your right hand and right eye to look at your patient’s right eye, and vice versa. When using a PanOptic, steady the patient’s head as usual and approach them from 6 inches away at a 15-20° angle. Do not worry about getting too close to the patient during this exam. You must be as close as possible to perform a detailed examination.

Tell your patient where to look. Instruct your patient to gaze straight ahead and past you. Providing your patient with a specific spot to steady their gaze will relax the patient and prevent hurried eye movement that will disrupt your examination.

Look for the red reflex. Hold the ophthalmoscope, still up to your eye, at about arm’s length from the patient. Shine the light into the patient’s right eye at about 15° from the center of the eye, and watch for the pupil to shrink. Then check to see if there is a red reflex. The red reflex is the reddish glint of light in the eye’s pupil caused by reflection of light off the retina, like what you see in a cat's eye in the dark. Absence of a red reflex can mean there is a problem with the eye. As you look through the scope for the red reflex, you may need to adjust focus a bit depending on your own eyesight.

Performing the Examination

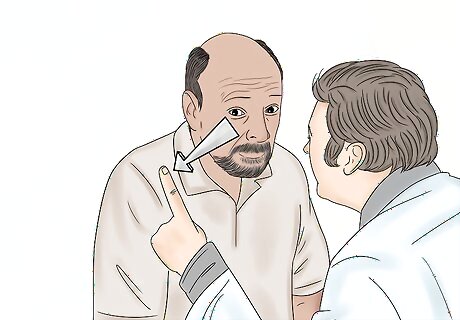

Use the red reflex as a guide to start your exam of the retina. Moving your head, hand and scope as one unit, slowly follow the red reflex in closer to the patient’s right eye. Stop moving forward when your forehead comes into contact with your left thumb. Following the red reflex should direct you to being able to visualize the retina. You may need to focus your scope to bring features of the eye into focus. Use your forefinger to turn the lens dial, as needed.

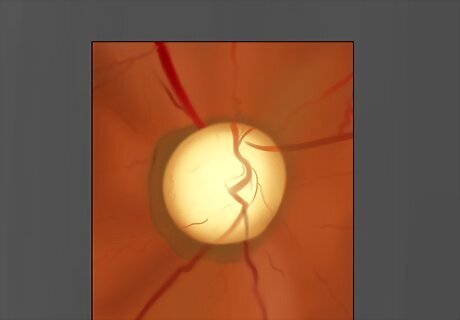

Observe the optic disc. Use a “pivoting” motion to angle the ophthalmoscope left and right, and up and down. Observe the disc for color, shape, contour, margin clarity, cup-to-disc ratio, and condition of the blood vessels. If you have difficulty finding the optic disc, locate a blood vessel and follow it. Blood vessels will lead you to the optic disc. Look for cupping or swelling (edema) of the optic disc.

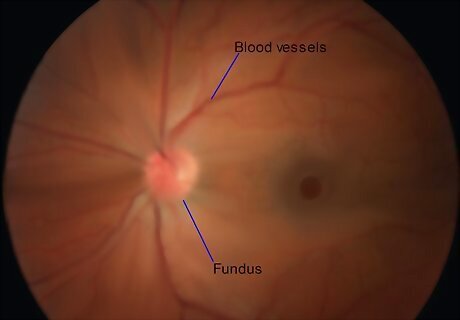

Check the blood vessels and fundus for pathology. Pivot to examine the four quadrants of the eye: superotemporal (up and out), superonasal (up and in), inferotemporal (down and out), and inferonasal (down and in). Proceed slowly and carefully examine for signs of disease. This is by no means a complete listing, and you should use clinical judgment and knowledge during your exam, but watch for the following: AV nicking Hemorrhages or exudates Cotton wool spots Roth spot Retinal or venous occlusion Emboli

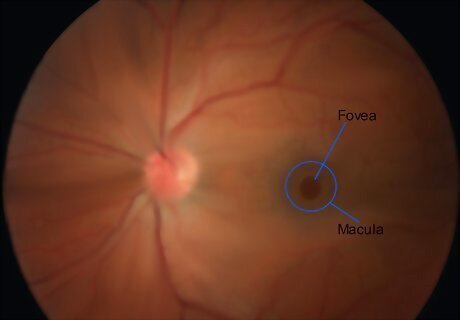

Evaluate the macula and fovea last. Instruct your patient to look directly into the light. This can be uncomfortable, which is why it’s saved for the end of the exam. The macula is responsible for central, focused vision, so visual acuity tests often indicate healthy or dysfunctional macula. The macula appears as a darker disc approximately in the center of the retina, with the fovea a bright point in the middle of the macula.

Assess the other eye. Repeat the procedure on the other eye, and remember to switch which hand and eye you use for examination. Though some illnesses cause changes in both eyes, other problems may only show up in one eye; it’s important to observe both carefully.

Educate your patient. Explain any abnormalities that you noticed to your patient, what it might mean, and any further actions they should take. If mydriatic drops were used, instruct your patient they may experience light sensitivity and blurred vision for several hours. Remind them they should have someone drive them home. Provide them disposable sunglasses if they did not bring their own.

Document your findings. Document everything that you saw in your examination, including specific notes on any abnormalities. It is often helpful to include pictures as visual cues to remember what you saw, and to compare to that patient’s later exams to see how things have changed.

Comments

0 comment